BRR: Tell us about Reon’s background and your current business model.

MHK: Reon was set up about six years ago to work on innovative models in energy as part of Dawood Hercules group. We had a vision of moving towards more sustainable means of addressing our energy needs. We also recognized that spending millions of dollars in setting up a power plant, then laying a thousand kilometers of cable to send that power to another end of the country is very inefficient. The longer the length of the cable, the higher the losses.

Our two mandates were renewable power that was clean and sustainable, and, distributed power. We started experimenting with different technologies such as biogas, solar tube-wells, solar lanterns and we also started installing solar power for industrial customers. Naturally, as the startup evolved, we found that industrial solar showed great promise because the segment was paying very high prices, faces load-shedding, has an unstable network, and received low-quality power. The industry was feeling the pinch. This was the time when exports were declining, gas was short, and we did not have a lot of power in the system.

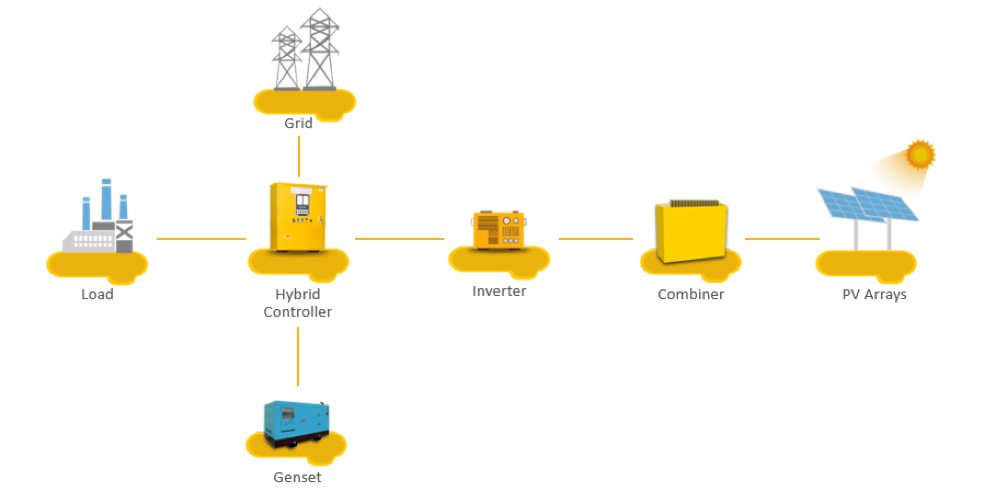

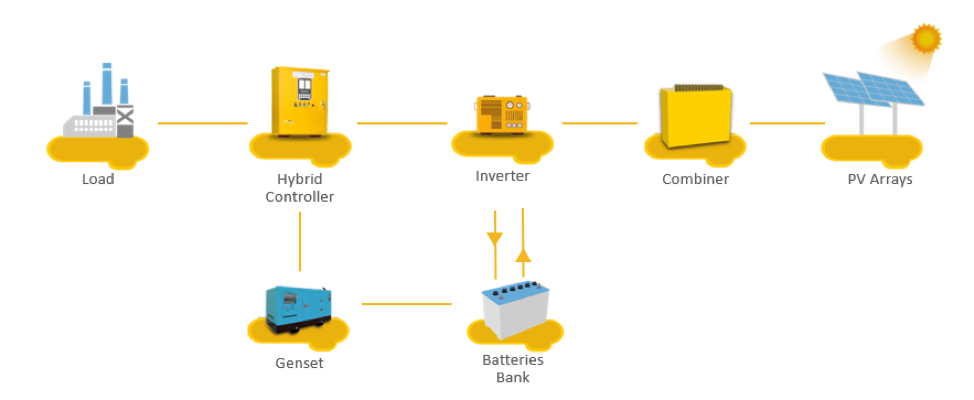

So today, we are the largest installer of solar and solar-hybrids (for consistent supply, solar is either balanced with the grid, with batteries, or with diesel/gas generators where a grid is not available) for commercial and industrial customers.

BRR: What is the market size of solar, the market demand and which segments are you currently targeting?

MHK: Solar sizing is limited by two things: first, demand as measured by customer size, and second is the availability of space. The only problem with solar is it takes too much space so it either needs rooftops or land to put in a solar plant. Based on both those constraints, roughly 2-2.5GW is where the industry puts the market size in Pakistan. This is only for the large commercial and industrial base where each industry should be able to absorb at least a MW of power.

The demand for electricity would be around 23 GW, and the installed base is slightly below that. We know that large portions of that are consumer demand, and around 30-40 percent is commercial and industrial. On overall demand basis, that’s around 8GW of power which can be absorbed by industries. A large part of that is the long-tail which is the SMEs. That market requires a different business model. We realize that there is a big problem to solve when it comes to SMEs as they have limited access to banking and financial products to be able to afford investment into solar.

Our other focus is the customer on the distribution side so, for instance, telecom customers who have telecom base transceiver station (BTS) sites. In Pakistan, we have roughly about 35000 BTS sites and we are the largest installer of solar systems on them. On a typical site, there are multiple sources of power because for telecom companies, availability is crucial. When the tower doesn’t have power, it loses revenue. We are using a combination of solar, lithium-ion batteries, grid power, and even diesel generators to assure 100 percent availability. The diesel generator is the misfit here and we are trying to eliminate that by enhancing the size of solar and batteries.

BRR: What about local manufacturing? Do you see that happening for solar, and/or for batteries? Are there any local ancillary industries involved?

MHK: We have very limited manufacturing base for solar in Pakistan. For any manufacturer to start competing with the large Chinese players, he needs demand in large volumes which is the biggest limitation here. In batteries as well, our manufacturing caters to the old lead-acid batteries which have a very short shelf life so has to be replaced every year or couple of years which is a big cost for the customer. Secondly, there is the depth of discharge—only 50-60 percent of the capacity available on the battery is used.

As for lithium-ion batteries, the manufacturing process is very expensive for which large investment is needed, and requires a supply chain. You need access to specialist material used which are only available in certain parts of the world such as lithium (Chile and Argentina) and cobalt (Congo). You may also need to acquire certain patented formulas. However, I’m sure when the volumes reach a certain level, there will be an investment.

BRR: At what volumes do you think these investments can come in?

MHK: My estimate is roughly around 200MW of guaranteed demand. That’s the minimum level you need to reach to be able to put up a panel manufacturing factory. But there is no guarantee that it will produce a product cheaper than China. In China, the largest manufacturer, Jinko Solar, last year manufactured around 11GW. We are talking about minimum viability at 200 MW so there is a massive difference in scale. It will be very hard for local players without protection early on from the government to be able to scale to that level and compete with the Chinese.

BRR: Tell us about some of the projects you have undertaken in Pakistan.

MHK: Currently, we are working on 30 MW of distributed solar. Easily the largest is about 12.5MW captive project for Fauji Cement where solar is synced with grid—they will be saving a lot of money. We have a 5MW project in Thar where we will be selling power to Sindh Coal Mining Company for a 15-year period. We also have several other megawatt plus scale projects. This is an industry of exponential growth. The number of projects we are doing this year is 3 times what we did last year.

BRR: Aside from structural issues within the energy sector which are well-documented, what other challenges are you seeing?

MHK: Right now, I see repeating a huge mistake that we made in the past. In the 90s, we set up furnace oil plants on technology which was dead-end and was environmentally polluting. It was also the most expensive fuel and the consumer has been paying the cost of that lopsided decision. Now again, to the detriment of everyone, we have seen a mad rush toward fossil fuel on long term take or pay contracts. We have locked 25-30 years power purchase agreements (PPAs) where not only the capacity charge is guaranteed but the energy charge is also guaranteed. This means we have to pay for the fuels when the plants are not running.

In a world where the energy market is moving toward wholesale, which means, you sell your power to the wholesale market and you get what the market is going to pay you at a certain time, we are handing out 30-year PPAs as a nation. And that too in an environment where technology is progressing at a very fast pace.

For large scale power plants, it takes 4-5 years to get everybody to agree on the technology, the money, the debt terms, the regulatory processes, etc. By that time, the technology has moved on. Compare that to renewable distributed power. First: the project can happen within six months of agreeing all the details—from the time when the customer starts thinking about it to getting the power in the system could be less than one year. Second: we are injecting power into the grid. We know the transmission and distribution system is overloaded. NEPRA report says 80 percent of transformers are overloaded. We have all this power which cannot be evacuated because we don’t have the transmission capacity. And the great thing about distributive power is that you can go to the source and get past all that distribution and transmission constraint and evacuate power at the local level.

Going forward, the government should shorten the length of the contract. There has to be some guarantee for people to make the investments but after that period has lapsed, which can be 10-15 years, the investor should have to sell it to the wholesale market. We know the government is keen on setting a wholesale power market. The Central Power Purchasing Agency (CPPA) has already received the first license to act as the wholesale market operator in the country. This needs to be accelerated.

BRR: Solar tariffs are significantly lower, so why aren’t we going solar?

MHK: Yes, solar and wind, both at the local level and the utility level are the cheapest. The short answer is uncertainty. In an uncertain market, people will keep the cash and not invest it. Similarly, in Pakistan, over the past 6-8 months, we have gone through elections, even before that, we were in a fairly uncertain environment. Since elections, people are waiting for policies to be announced to come up with a plan.

As a nation, we have been playing safe and there is a reluctance to go to something new, even though it’s not new around the world. In Germany, these plants have been running for 30 years, still operating at 80 percent capacity. It’s a safe, robust technology but in Pakistan, since we are so behind the curve, the comfort level the industrial sector has in this technology is lower. It’s only after players such as Fauji Cement have taken the first step to install 12.5MW of Solar Power that others are exploring it as a big move in the local industry. When they see a plant at this scale, getting integrated at a local level successfully, then you will see momentum.

BRR: Can the existing captive power plants be switched to solar?

MHK: One of the things we specialize in is integrating solar and battery with the client’s legacy power access. We recently started a 2MW extension project for Kohinoor Textile Mill. Local fuel sources such as gas and furnace oil and solar fit seamlessly with them. Most of our projects have an element of integration for existing captive power plants.

BRR: Prices of solar technology have come down. Where do you see the prices of solar moving?

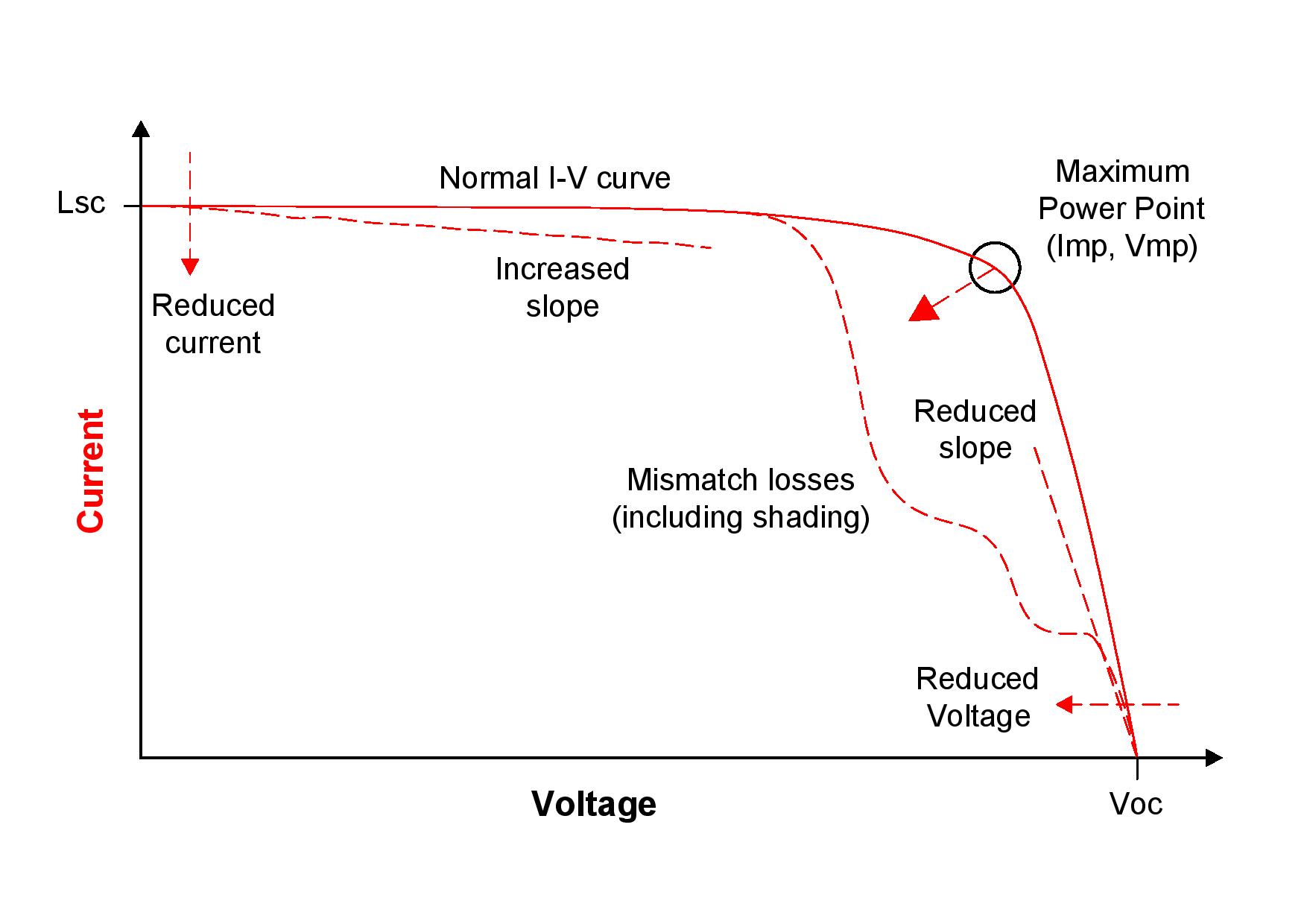

MHK: There are two elements of the prices coming down in the past few years. One is that panels are getting more efficient. For the same space, you can pack in more power, so they are becoming land and cost-efficient. Secondly, as they scale, production efficiencies kick in and prices come down. In terms of efficiencies, we are approaching the maximum which is around 30 percent for the current set of products. Volumes are also significantly up.

Over the short term, we see prices stabilizing at this level at least for the next 3-4 quarters. In the long term, the projection is downward but not at the same pace as we previously witnessed because of the cap on the efficiency of these panels. Unless there is new technology which can be made commercially available, the cost curve will become less steep.

But as volumes grow costs of production declines. This is called the Swanson’s law which says, if solar capacity is doubled, costs of production will be down by 18-20 percent. The similar law applies for batteries. There is a big surge in demand for batteries where a lot of countries are moving toward battery-run electric cars and maybe phasing combustion engines out completely. Right now, 90 percent of all investments are going toward lithium-ion batteries (which we use in our mobiles). It’s scalable and we are betting big on it.

BRR: Why hasn’t off-grid electrification picked up given such a large population in the country has no access?

MHK: Nearly, 60 million people are off-grid with no access to any sort of network. There is a clear lack of policy in that area. We are talking about a population the size of Turkey which is without power at this point. If you consider, Pakistan’s average consumption is 471 kWh per capita per year. If you want to bring those people up to the level on the same system, it would require at least $2 billion annually in terms of power generation cost. To extend the distribution and transmission system to those people will be disproportionately more expensive. There is a reason why the network is not there.

The only viable way to solve that problem is through renewable power. It can be solar-battery hybrid solutions and island mini-grids which are distributed grids set up for a particular village or district that is off-grid. These grids have solar power potentially combined with biomass and other renewable sources at the local level.

Second, we need to follow Bangladesh’s example. The country set up a Rural Electrification Board specifically for the off-grid population. The sole purpose of that organization is to provide power to areas where it is not available. The country has reached a penetration level of 85 percent compared to Pakistan at 70 percent.

So, the government needs to clarify the policy. Secondly, the current incentives are toward IPPs who for decades have received tax holidays and special dividend rates for more investment into large scale power projects. I believe, there should be even better incentivization for the off-grid investors. It is cheaper, more effective, it gets past the transmission and distribution problem, and it’s the only solution available to the off-grid population.